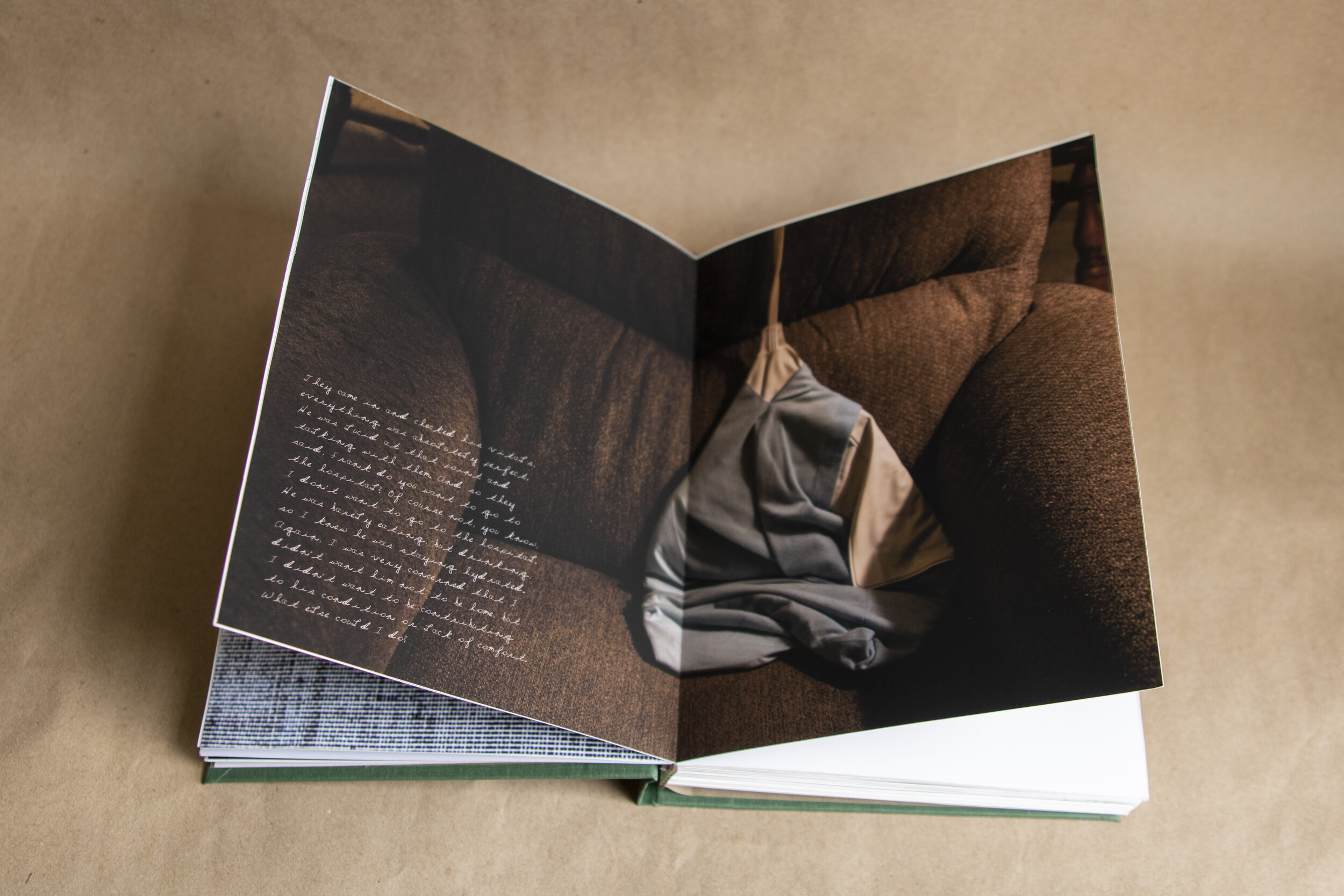

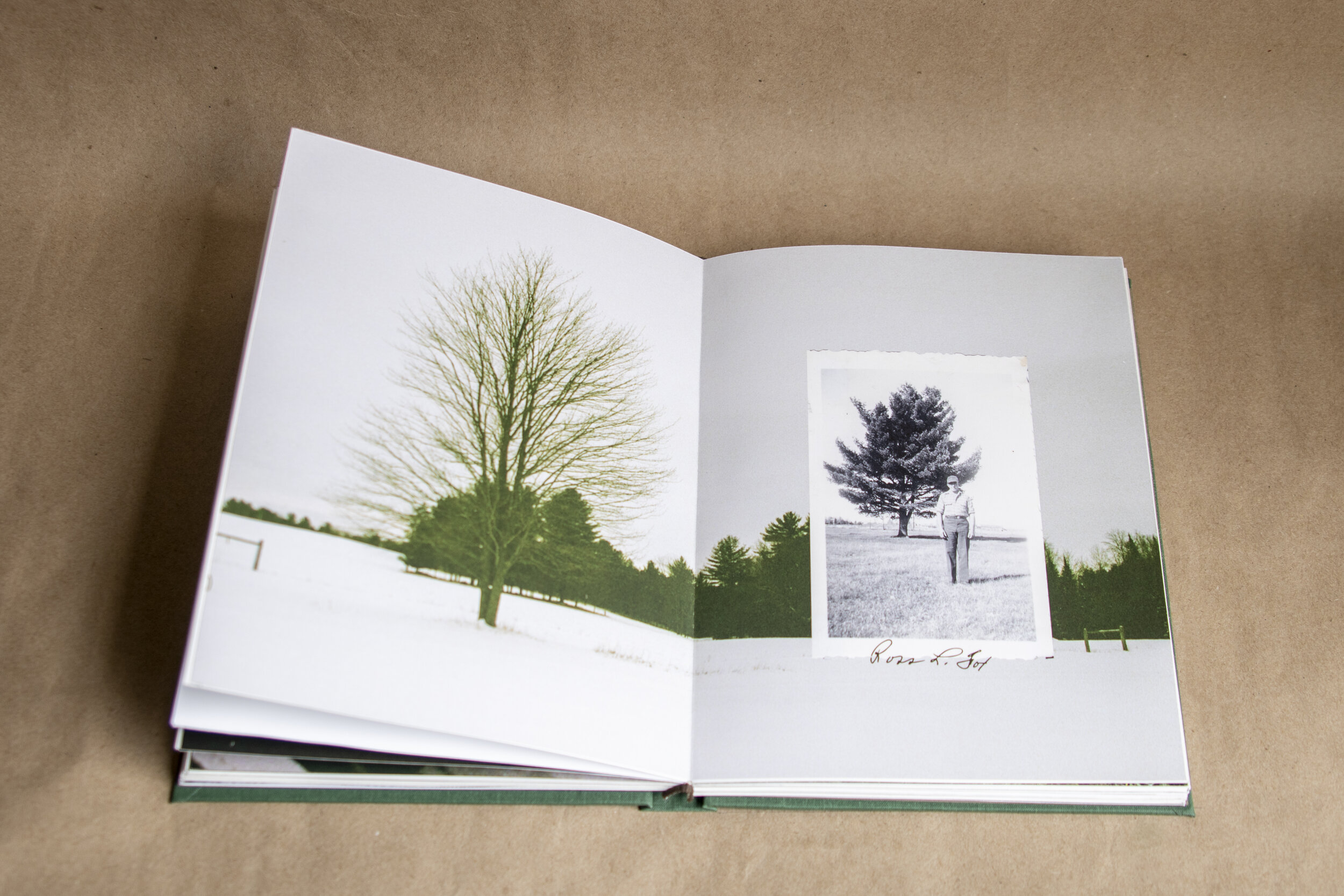

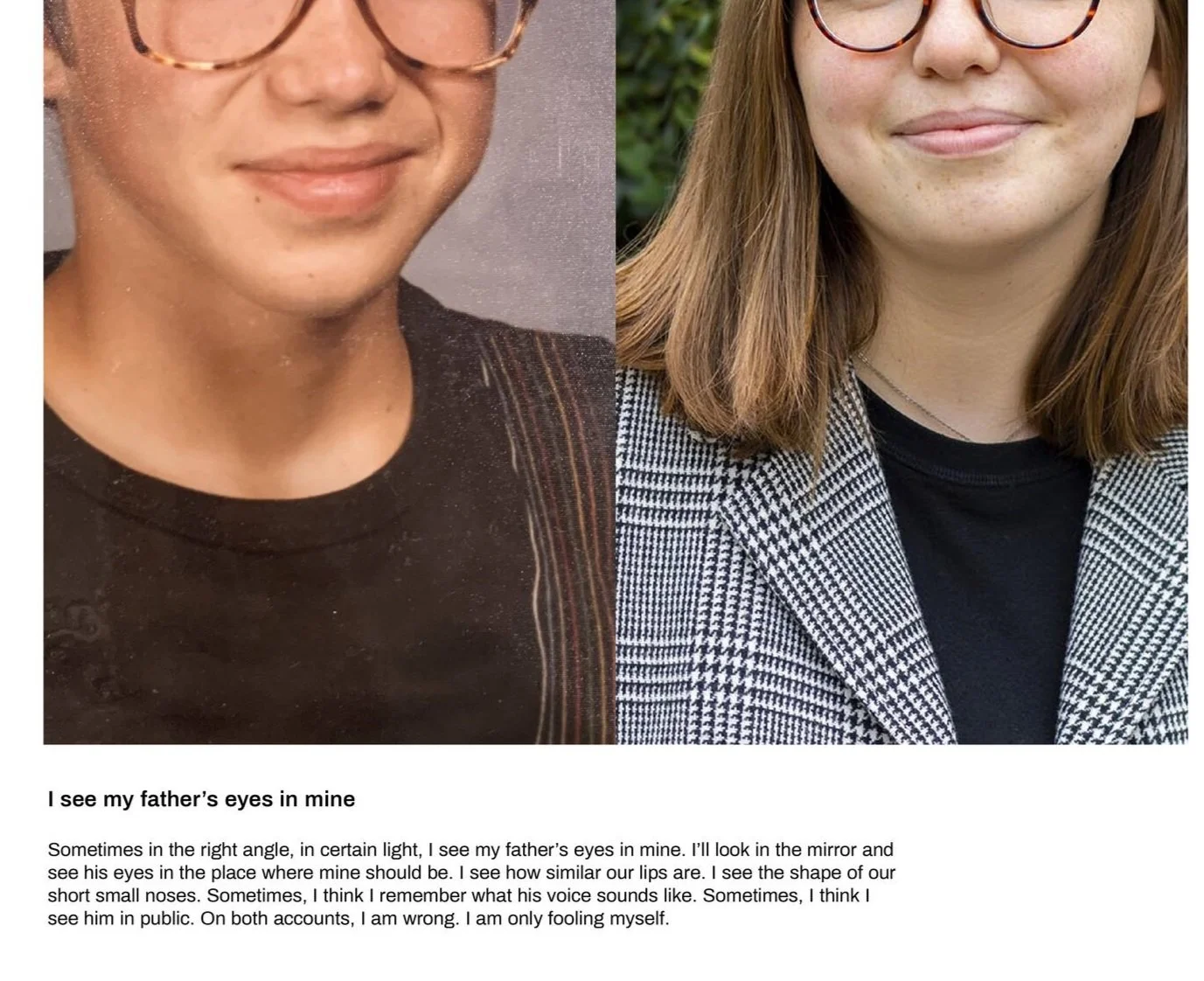

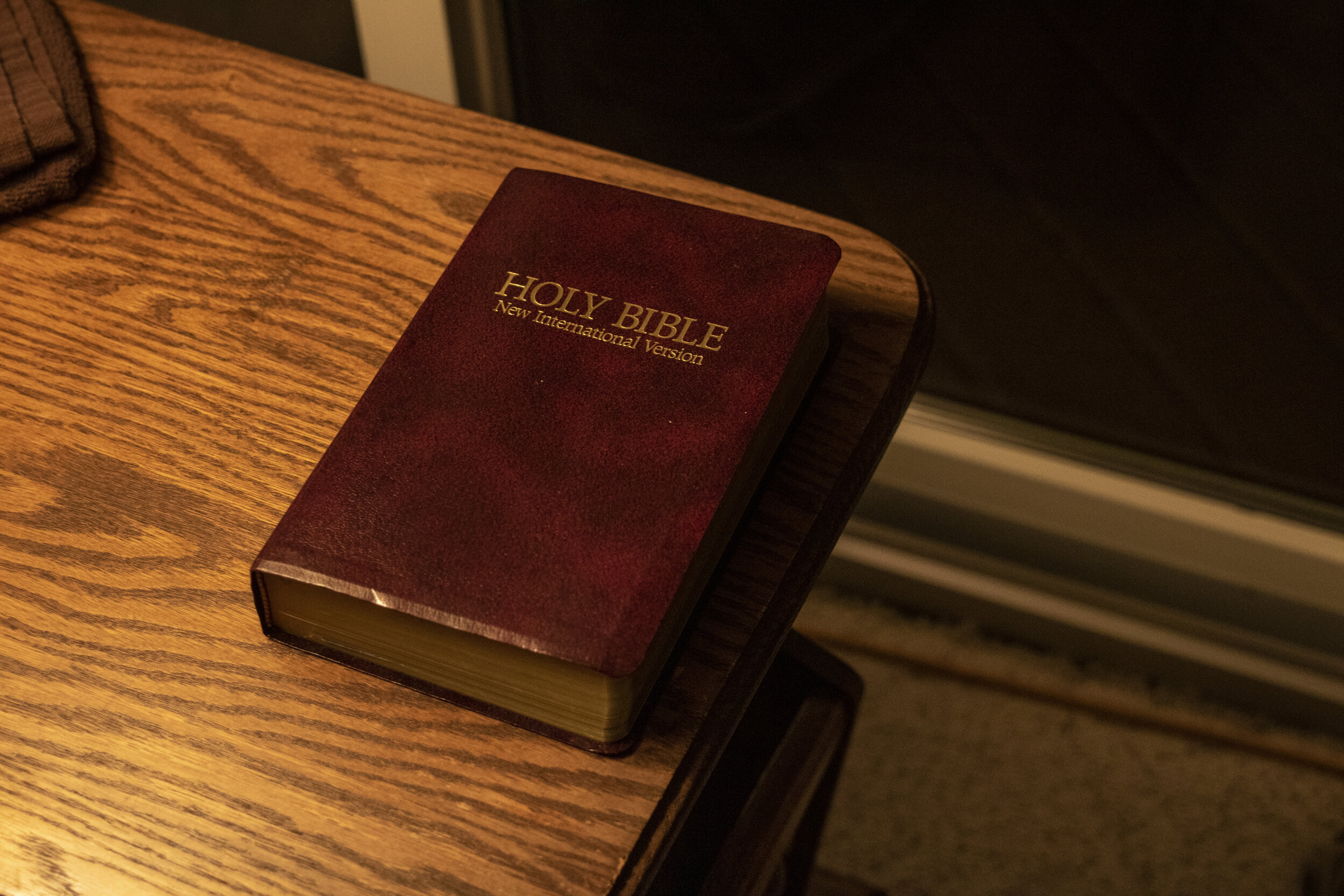

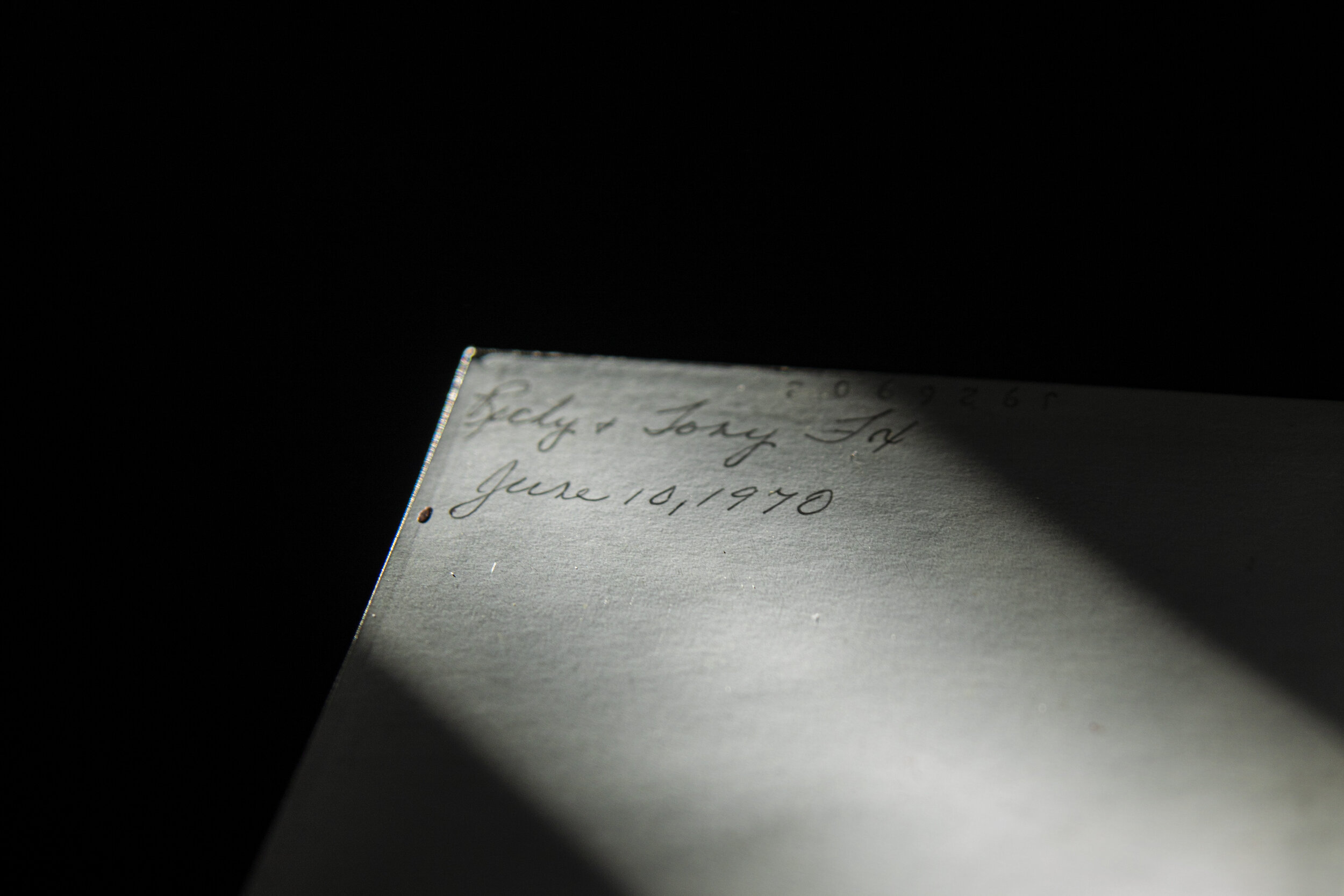

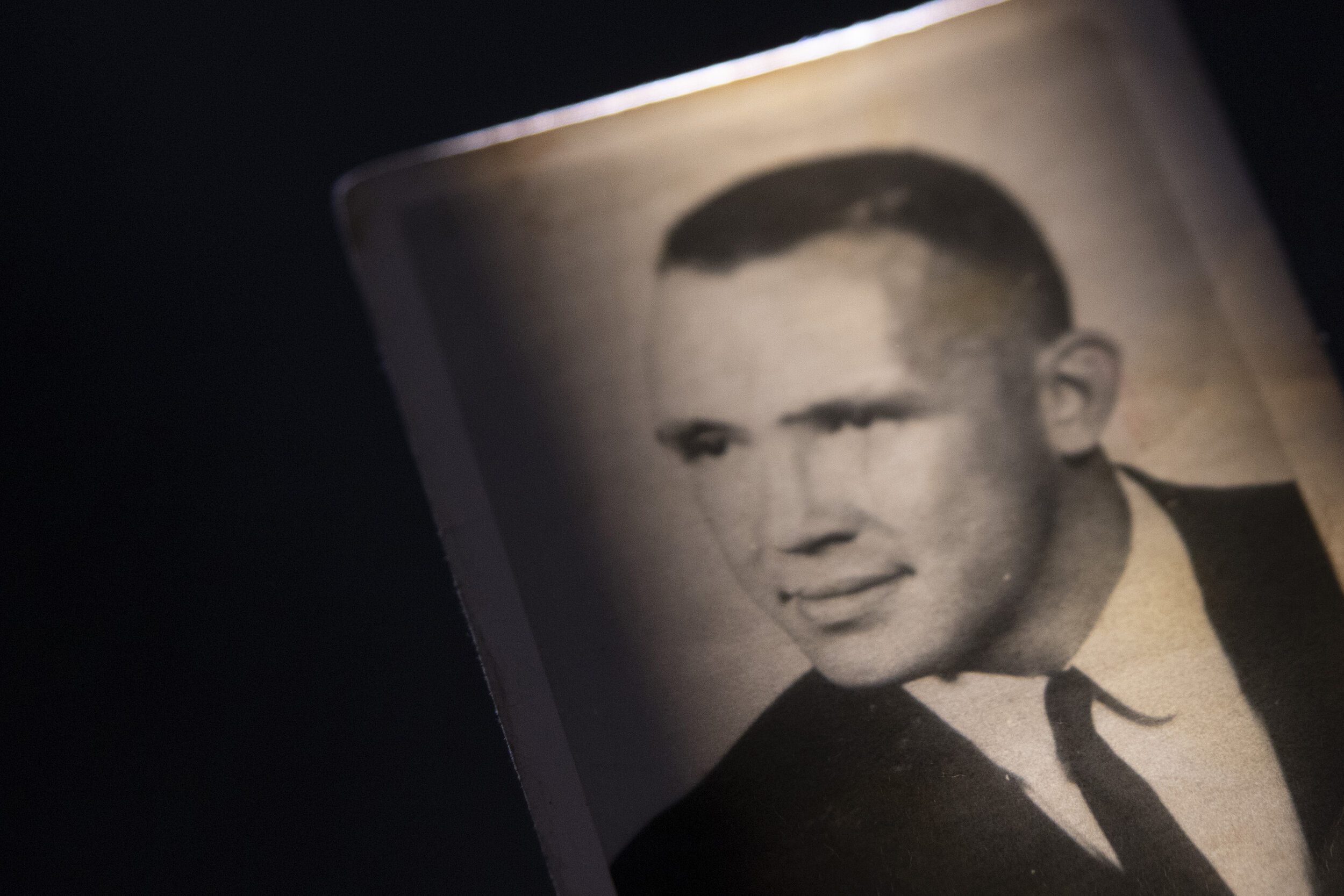

The Time We Spent explores the relationships between photography, grief, and memory. Narrated by my grandma’s own words, I use photographs to construct a trace of my grandparents’ lives from both the past and present. I curate archival photographs, new photographs I’ve captured, handwriting, stories, and physical memorabilia in order to highlight their increased social value and fragility in a time of personal grief. Through multiple interviews with my grandma, I’ve strived to cultivate a culture of listening and storytelling in the wake of my grandpa’s absence. Activating photography as a form of social practice has allowed me to engage with and understand my grandparents’ lives and memories both photographically and orally.

My hope for this book is to allow others to re-experience a past that is not their own. I welcome viewers to seek out reflections of themselves, their own families, and stories in my book. The pandemic restrictions called my social habits and sense of familial bonds into question. It stirred in me an urgency to archive the past and document the present. I found both healing in the observation of the past and catharsis in the creation of the new.

Recipient of the BFA Integrative Project Award for the Class of 2021

Exhibited in the 2021 Stamps School Senior Exhibition

Published by The Michigan Daily

The Time We Spent

9” x 7” Drum Leaf Book

BFA Senior Thesis

August 2020–April 2021

Early Ideation & Experimentation

The early steps in my creative process included exploring the book form as a medium, binding structures, and obfuscation of photographs. This project taught me how to cultivate creative stamina through a daily practice of making.

Research

During a time in which social interactions are limited and rigid, it is vital to hone a mode of connection that is meaningful and rich. In my research I explored, how can we learn from the oldest among us in this unique moment of a pandemic? How can photography be used to document their stories, experiences, and wisdom?

COVID has created a sharp break from our previous life activities, resulting in feelings of isolation, anonymity, and loneliness. As of November 2020, more than 250,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the United States, a majority of which were 65 years or old. In such incomprehensible circumstances, the eldery are facing increased loneliness and isolation, on top of their increased vulnerability to this virus. Such an insurmountable loss of lives equates to a loss of stories, experiences, and wisdom. The wisdom and experiences from the elderly often reveal themselves through the stories they share about family photographs. My research analyzed how a study conducted in an Irish assisted-living facility found the construction of life story books gave elderly patients a medium to prompt their own storytelling and reflection of their lives; likewise, giving them space to talk about their experiences. These autobiographical books included photographs, personal essays, and other memorabilia pertinent to the person’s life in order to give the patients a sense of identity and a holistic view of their lives. The goal of the books was twofold, to allow the elderly person a space to share their memories and life experiences, but also allow these personal experiences to inform and be the basis of individualized patient care at the facility.

Similarly, I discovered another source that noted the ability of photographs to help build and validate our identities. This is called the identity negotiation theory. This theory explains how we use photography to build our own identity and our family’s identity as it relates to our culture, gender, personality, ethnicity, our roles, and relationships. Photographs are key to narrative development and identity building. In other words, they are a powerful tool to elicit stories to be recounted, and those stories reveal the identities of both the individual storyteller and the family. My research indicates that such family photography can be defined as a social practice that revolves around saving memories of the past, in a physical visual form, for future communal reminiscing.

Likewise, Erin Kirkland, Art Streiber, and Deanna Dikeman approach their photography with a social practice lens. The act of repeatedly capturing photographs of everyday life moments like sitting, waving goodbye, or waving hello speak to the broader social bonds that are so vital to our lives, especially now given the unique circumstances of the pandemic. In particular, Dikeman exemplified how photographing small rituals and everyday gestures can culminate to tell the narrative of multiple generations. For three decades she repetitively recorded life as it was, as it happens. This type of practice reflects on the social bonds in families and results in photographs with high communicative and emotional value. They turn challenging social moments in life, such as visiting loved ones during a pandemic and saying goodbye, into art. By photographing these tough social moments in life, they are able to investigate familial bonds everyone can relate to. Family photographs and the albums they so often reside in create a communal space to discuss social issues within the family unit, such as death, grief, and aging.

The core of my research has illuminated that photographs are essential to people due to its exceptional communicative, visual, and emotional appeal. Beyond the art and design world, family photography can speak volumes in the fields of material and cultural studies, as well as visual anthropology. Yet, very little research has been done in regards to interpersonal communication and storytelling as a form of visual communication by way of printed photographs. In other words, photography is a medium that can be used to learn more about those we surround ourselves with most, family. Especially during the COVID era, family photography offers a way to engage with and understand memories unlike any other medium. Today, we cultivate a digital performative narrative of our lives on public social media platforms. The printed photograph and the family photo album are a quickly disappearing phenomenon. In my future creative work, I seek to inspire others to take a step back from the digital world and remember the roots of photography, the family photo album in its material form.

Bookbinding Process

The second major discovery I made was finding a medium that I love so much, book arts. It correlated so well to these themes at the core of my creative practice- photography, archiving, documenting, and storytelling. Since this project was mainly inspired by the loads of old, printed film photographs from my grandma, I felt compelled to create something that would have a physical presence. I spent a great deal of time researching the concept of the family photo albums and changing image culture. Not many people print physical photographs anymore. To me, physical copies of photographs are so compelling to look at, to hold, to admire, to ponder on. As well as being critical in the grieving process for me. They're tangible traces of existence. I felt similarly enthralled by the physical albums these old family photos were housed in; they felt so book-like. I began exploring various textures and tactile elements like the pockets on the pages and the vellum inlay on the cover. This led me down a path of collecting and retelling stories as art. The book form spoke to me as this collection of things that could be bound together, and slowly tell an unfolding narrative, page by page. Of the course of IP I attended two different book-making workshops and enjoyed them greatly. I learned so much of the craft-based skills and techniques that my solely online research could not provide. Albeit the workshops were over Zoom, the real life instruction made a huge difference. I think my final project form works to house and honor these memories and stories outside of the noise of the internet. It has become this very intentional object I found so much joy in while I was creating under a purely digital class structure and world. Above all, making something with my hands and trying and learning something was very rewarding.